Roman Empire

Literature[edit] Main article: Latin literature

See also: Roman historiography, Church Fathers, and Latin poetry

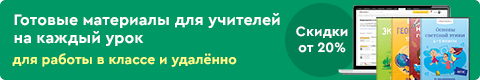

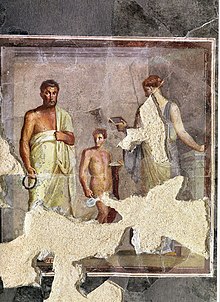

A fresco in Pompeii depicting a poet (thought to be Euphorion) and a female reading a diptych

Statue in Constanța, Romania (the ancient colony Tomis), commemorating Ovid's exile

In the traditional literary canon, literature under Augustus, along with that of the late Republic, has been viewed as the "Golden Age" of Latin literature, embodying the classical ideals of "unity of the whole, the proportion of the parts, and the careful articulation of an apparently seamless composition."[613] The three most influential Classical Latin poets—Virgil, Horace, and Ovid—belong to this period. Virgil wrote the Aeneid, creating a national epic for Rome in the manner of the Homeric epics of Greece. Horace perfected the use of Greek lyric metres in Latin verse. Ovid's erotic poetry was enormously popular, but ran afoul of the Augustan moral programme; it was one of the ostensible causes for which the emperor exiled him to Tomis (present-day Constanța, Romania), where he remained to the end of his life. Ovid's Metamorphoses was a continuous poem of fifteen books weaving together Greco-Roman mythology from the creation of the universe to the deification of Julius Caesar. Ovid's versions of Greek myths became one of the primary sources of later classical mythology, and his work was so influential in the Middle Ages that the 12th and 13th centuries have been called the "Age of Ovid."[614]

The principal Latin prose author of the Augustan age is the historian Livy, whose account of Rome's founding and early history became the most familiar version in modern-era literature. Vitruvius's book De Architectura, the only complete work on architecture to survive from antiquity, also belongs to this period.

Latin writers were immersed in the Greek literary tradition, and adapted its forms and much of its content, but Romans regarded satire as a genre in which they surpassed the Greeks. Horace wrote verse satires before fashioning himself as an Augustan court poet, and the early Principate also produced the satirists Persius and Juvenal. The poetry of Juvenal offers a lively curmudgeon's perspective on urban society.

The period from the mid-1st century through the mid-2nd century has conventionally been called the "Silver Age" of Latin literature. Under Nero, disillusioned writers reacted to Augustanism.[615] The three leading writers—Seneca the philosopher, dramatist, and tutor of Nero; Lucan, his nephew, who turned Caesar's civil war into an epic poem; and the novelist Petronius (Satyricon)—all committed suicide after incurring the emperor's displeasure. Seneca and Lucan were from Hispania, as was the later epigrammatist and keen social observer Martial, who expressed his pride in his Celtiberian heritage.[83] Martial and the epic poet Statius, whose poetry collection Silvae had a far-reaching influence on Renaissance literature,[616] wrote during the reign of Domitian.

The so-called "Silver Age" produced several distinguished writers, including the encyclopedist Pliny the Elder; his nephew, known as Pliny the Younger; and the historian Tacitus. The Natural History of the elder Pliny, who died during disaster relief efforts in the wake of the eruption of Vesuvius, is a vast collection on flora and fauna, gems and minerals, climate, medicine, freaks of nature, works of art, and antiquarian lore. Tacitus's reputation as a literary artist matches or exceeds his value as a historian;[617] his stylistic experimentation produced "one of the most powerful of Latin prose styles."[618] The Twelve Caesars by his contemporary Suetonius is one of the primary sources for imperial biography.

Among Imperial historians who wrote in Greek are Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the Jewish historian Josephus, and the senator Cassius Dio. Other major Greek authors of the Empire include the biographer and antiquarian Plutarch, the geographer Strabo, and the rhetorician and satirist Lucian. Popular Greek romance novels were part of the development of long-form fiction works, represented in Latin by the Satyricon of Petronius and The Golden Ass of Apuleius.

From the 2nd to the 4th centuries, the Christian authors who would become the Latin Church Fathers were in active dialogue with the Classical tradition, within which they had been educated. Tertullian, a convert to Christianity from Roman Africa, was the contemporary of Apuleius and one of the earliest prose authors to establish a distinctly Christian voice. After the conversion of Constantine, Latin literature is dominated by the Christian perspective.[619] When the orator Symmachus argued for the preservation of Rome's religious traditions, he was effectively opposed by Ambrose, the bishop of Milan and future saint—a debate preserved by their missives.[620]

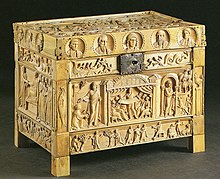

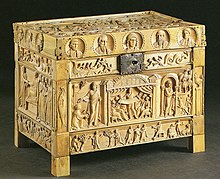

Brescia Casket, an ivory box with Biblical imagery (late 4th century)

In the late 4th century, Jerome produced the Latin translation of the Bible that became authoritative as the Vulgate. Augustine, another of the Church Fathers from the province of Africa, has been called "one of the most influential writers of western culture", and his Confessions is sometimes considered the first autobiography of Western literature. In The City of God against the Pagans, Augustine builds a vision of an eternal, spiritual Rome, a new imperium sine fine that will outlast the collapsing Empire.

In contrast to the unity of Classical Latin, the literary esthetic of late antiquity has a tessellated quality that has been compared to the mosaics characteristic of the period.[621] A continuing interest in the religious traditions of Rome prior to Christian dominion is found into the 5th century, with the Saturnalia of Macrobius and The Marriage of Philology and Mercury of Martianus Capella. Prominent Latin poets of late antiquity include Ausonius, Prudentius, Claudian, and Sidonius Apollinaris. Ausonius (d. c. 394), the Bordelaise tutor of the emperor Gratian, was at least nominally a Christian, though, throughout his occasionally obscene mixed-genre poems, he retains a literary interest in the Greco-Roman gods and even druidism. The imperial panegyrist Claudian (d. 404) was a vir illustris who appears never to have converted. Prudentius (d. c. 413), born in Hispania Tarraconensis and a fervent Christian, was thoroughly versed in the poets of the Classical tradition,[622] and transforms their vision of poetry as a monument of immortality into an expression of the poet's quest for eternal life culminating in Christian salvation.[623] Sidonius (d. 486), a native of Lugdunum, was a Roman senator and bishop of Clermont who cultivated a traditional villa lifestyle as he watched the Western empire succumb to barbarian incursions. His poetry and collected letters offer a unique view of life in late Roman Gaul from the perspective of a man who "survived the end of his world".[621][624]