Roman Empire

Literacy, books, and education[edit] |  | This article is missing information about the use of papyrus or parchment scrolls, which were very common before the invention of the codex. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (April 2017) |

Main article: Education in ancient Rome

Pride in literacy was displayed in portraiture through emblems of reading and writing, as in this example of a couple from Pompeii (Portrait of Paquius Proculo).

Estimates of the average literacy rate in the Empire range from 5 to 30% or higher, depending in part on the definition of "literacy".[521][522][523][524] The Roman obsession with documents and public inscriptions indicates the high value placed on the written word.[525][526][527][528][529] The Imperial bureaucracy was so dependent on writing that the Babylonian Talmud declared "if all seas were ink, all reeds were pen, all skies parchment, and all men scribes, they would be unable to set down the full scope of the Roman government's concerns."[530] Laws and edicts were posted in writing as well as read out. Illiterate Roman subjects would have someone such as a government scribe (scriba) read or write their official documents for them.[523][531] Public art and religious ceremonies were ways to communicate imperial ideology regardless of ability to read.[532] The Romans had an extensive priestly archive, and inscriptions appear throughout the Empire in connection with statues and small votives dedicated by ordinary people to divinities, as well as on binding tablets and other "magic spells", with hundreds of examples collected in the Greek Magical Papyri.[533][534][535][536] The military produced a vast amount of written reports and service records,[537] and literacy in the army was "strikingly high".[538] Urban graffiti, which include literary quotations, and low-quality inscriptions with misspellings and solecisms indicate casual literacy among non-elites.[539][540][n 19][83] In addition, numeracy was necessary for any form of commerce.[526][541] Slaves were numerate and literate in significant numbers, and some were highly educated.[542]

Books were expensive, since each copy had to be written out individually on a roll of papyrus (volumen) by scribes who had apprenticed to the trade.[543] The codex—a book with pages bound to a spine—was still a novelty in the time of the poet Martial (1st century AD),[544][545] but by the end of the 3rd century was replacing the volumen[543][546] and was the regular form for books with Christian content.[547] Commercial production of books had been established by the late Republic,[548] and by the 1st century AD certain neighbourhoods of Rome were known for their bookshops (tabernae librariae), which were found also in Western provincial cities such as Lugdunum (present-day Lyon, France).[549][550] The quality of editing varied wildly, and some ancient authors complain about error-ridden copies,[548][551] as well as plagiarism or forgery, since there was no copyright law.[548] A skilled slave copyist (servus litteratus) could be valued as highly as 100,000 sesterces.[552][553]

Reconstruction of a writing tablet: the stylus was used to inscribe letters into the wax surface for drafts, casual letterwriting, and schoolwork, while texts meant to be permanent were copied onto papyrus.

Collectors amassed personal libraries,[554] such as that of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, and a fine library was part of the cultivated leisure (otium) associated with the villa lifestyle.[555] Significant collections might attract "in-house" scholars; Lucian mocked mercenary Greek intellectuals who attached themselves to philistine Roman patrons.[556] An individual benefactor might endow a community with a library: Pliny the Younger gave the city of Comum a library valued at 1 million sesterces, along with another 100,000 to maintain it.[557][558] Imperial libraries housed in state buildings were open to users as a privilege on a limited basis, and represented a literary canon from which disreputable writers could be excluded.[559][560] Books considered subversive might be publicly burned,[561] and Domitian crucified copyists for reproducing works deemed treasonous.[562][563]

Literary texts were often shared aloud at meals or with reading groups.[564][565] Scholars such as Pliny the Elder engaged in "multitasking" by having works read aloud to them while they dined, bathed or travelled, times during which they might also dictate drafts or notes to their secretaries.[566] The multivolume Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius is an extended exploration of how Romans constructed their literary culture.[567] The reading public expanded from the 1st through the 3rd century, and while those who read for pleasure remained a minority, they were no longer confined to a sophisticated ruling elite, reflecting the social fluidity of the Empire as a whole and giving rise to "consumer literature" meant for entertainment.[568] Illustrated books, including erotica, were popular, but are poorly represented by extant fragments.[569]

Primary education

[edit]

A teacher with two students, as a third arrives with his loculus, a writing case that would contain pens, ink pot, and a sponge to correct errors[570]

Traditional Roman education was moral and practical. Stories about great men and women, or cautionary tales about individual failures, were meant to instil Roman values (mores maiorum). Parents and family members were expected to act as role models, and parents who worked for a living passed their skills on to their children, who might also enter apprenticeships for more advanced training in crafts or trades.[571] Formal education was available only to children from families who could pay for it, and the lack of state intervention in access to education contributed to the low rate of literacy.[572][573]

Young children were attended by a pedagogus, or less frequently a female pedagoga, usually a Greek slave or former slave.[574] The pedagogue kept the child safe, taught self-discipline and public behaviour, attended class and helped with tutoring.[575] The emperor Julian recalled his pedagogue Mardonius, a Gothic eunuch slave who reared him from the age of 7 to 15, with affection and gratitude. Usually, however, pedagogues received little respect.[576]

Primary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic might take place at home for privileged children whose parents hired or bought a teacher.[577] Others attended a school that was "public," though not state-supported, organized by an individual schoolmaster (ludimagister) who accepted fees from multiple parents.[578] Vernae (homeborn slave children) might share in-home or public schooling.[579] Schools became more numerous during the Empire and increased the opportunities for children to acquire an education.[573] School could be held regularly in a rented space, or in any available public niche, even outdoors. Boys and girls received primary education generally from ages 7 to 12, but classes were not segregated by grade or age.[580] For the socially ambitious, bilingual education in Greek as well as Latin was a must.[573]

Quintilian provides the most extensive theory of primary education in Latin literature. According to Quintilian, each child has in-born ingenium, a talent for learning or linguistic intelligence that is ready to be cultivated and sharpened, as evidenced by the young child's ability to memorize and imitate. The child incapable of learning was rare. To Quintilian, ingenium represented a potential best realized in the social setting of school, and he argued against homeschooling. He also recognized the importance of play in child development,[n 20] and disapproved of corporal punishment because it discouraged love of learning—in contrast to the practice in most Roman primary schools of routinely striking children with a cane (ferula) or birch rod for being slow or disruptive.[581]

Secondary education

[edit]

Mosaic from Pompeii depicting the Academy of Plato

At the age of 14, upperclass males made their rite of passage into adulthood, and began to learn leadership roles in political, religious, and military life through mentoring from a senior member of their family or a family friend.[582] Higher education was provided by grammatici or rhetores.[583] The grammaticus or "grammarian" taught mainly Greek and Latin literature, with history, geography, philosophy or mathematics treated as explications of the text.[584] With the rise of Augustus, contemporary Latin authors such as Virgil and Livy also became part of the curriculum.[585] The rhetor was a teacher of oratory or public speaking. The art of speaking (ars dicendi) was highly prized as a marker of social and intellectual superiority, and eloquentia ("speaking ability, eloquence") was considered the "glue" of a civilized society.[586] Rhetoric was not so much a body of knowledge (though it required a command of references to the literary canon[587]) as it was a mode of expression and decorum that distinguished those who held social power.[588] The ancient model of rhetorical training—"restraint, coolness under pressure, modesty, and good humour"[589]—endured into the 18th century as a Western educational ideal.[590]

In Latin, illiteratus (Greek agrammatos) could mean both "unable to read and write" and "lacking in cultural awareness or sophistication."[521] Higher education promoted career advancement, particularly for an equestrian in Imperial service: "eloquence and learning were considered marks of a well-bred man and worthy of reward".[591] The poet Horace, for instance, was given a top-notch education by his father, a prosperous former slave.[592][593][594]

Urban elites throughout the Empire shared a literary culture embued with Greek educational ideals (paideia).[595] Hellenistic cities sponsored schools of higher learning as an expression of cultural achievement.[596] Young men from Rome who wished to pursue the highest levels of education often went abroad to study rhetoric and philosophy, mostly to one of several Greek schools in Athens. The curriculum in the East was more likely to include music and physical training along with literacy and numeracy.[597] On the Hellenistic model, Vespasian endowed chairs of grammar, Latin and Greek rhetoric, and philosophy at Rome, and gave teachers special exemptions from taxes and legal penalties, though primary schoolmasters did not receive these benefits. Quintilian held the first chair of grammar.[598][599] In the eastern empire, Berytus (present-day Beirut) was unusual in offering a Latin education, and became famous for its school of Roman law.[600] The cultural movement known as the Second Sophistic (1st–3rd century AD) promoted the assimilation of Greek and Roman social, educational, and esthetic values, and the Greek proclivities for which Nero had been criticized were regarded from the time of Hadrian onward as integral to Imperial culture.[601]

Educated women

[edit]

Portrait of a literary woman from Pompeii (ca. 50 AD)

Literate women ranged from cultured aristocrats to girls trained to be calligraphers and scribes.[602][603] The "girlfriends" addressed in Augustan love poetry, although fictional, represent an ideal that a desirable woman should be educated, well-versed in the arts, and independent to a frustrating degree.[604][605] Education seems to have been standard for daughters of the senatorial and equestrian orders during the Empire.[579] A highly educated wife was an asset for the socially ambitious household, but one that Martial regards as an unnecessary luxury.[602]

The woman who achieved the greatest prominence in the ancient world for her learning was Hypatia of Alexandria, who educated young men in mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, and advised the Roman prefect of Egypt on politics. Her influence put her into conflict with the bishop of Alexandria, Cyril, who may have been implicated in her violent death in 415 at the hands of a Christian mob.[606]

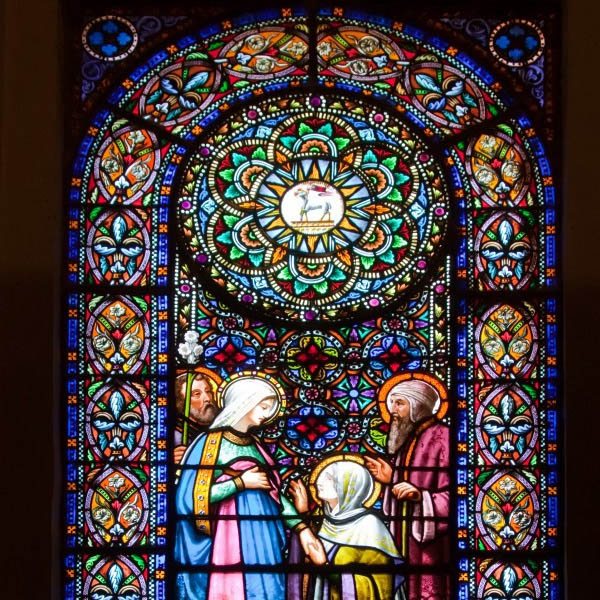

Shape of literacy

[edit] Literacy began to decline, perhaps dramatically, during the socio-political Crisis of the Third Century.[607] After the Christianization of the Roman Empire the Christians and Church Fathers adopted and used Latin and Greek pagan literature, philosophy and natural science with a vengeance to biblical interpretation.[608]

Edward Grant writes that:

With the total triumph of Christianity at the end of the fourth century, the Church might have reacted against Greek pagan learning in general, and Greek philosophy in particular, finding much in the latter that was unacceptable or perhaps even offensive. They might have launched a major effort to suppress pagan learning as a danger to the Church and its doctrines.

But they did not. Why not?

Perhaps it was in the slow dissemination of Christianity. After four centuries as members of a distinct religion, Christians had learned to live with Greek secular learning and to utilize it for their own benefit. Their education was heavily infiltrated by Latin and Greek pagan literature and philosophy... Although Christians found certain aspects of pagan culture and learning unacceptable, they did not view them as a cancer to be cut out of the Christian body.[609]

Julian, the only emperor after the conversion of Constantine to reject Christianity, banned Christians from teaching the Classical curriculum, on the grounds that they might corrupt the minds of youth.[599]

While the book roll had emphasized the continuity of the text, the codex format encouraged a "piecemeal" approach to reading by means of citation, fragmented interpretation, and the extraction of maxims.[610]

In the 5th and 6th centuries, due to the gradual decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire, reading became rarer even for those within the Church hierarchy.[611] However, in the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as Byzantine Empire, reading continued throughout the Middle Ages as reading was of primary importance as an instrument of the Byzantine civilization.[612]